How Much to Save

Savings creates choices.

Saving for college will give you choices

Research shows that, across income levels, students who have savings designated for college are more likely to attend and graduate. Overall, the study showed that children who were “expected” to attend college prior to graduating from high school and have at least $500 in college-designated savings are twice as likely to graduate from college than students with similar expectations but no savings.

The results vary by income groups but show results even with very modest savings accounts. For example, a student from a low- to moderate-income household (income less than $50,000) with savings between $1 and $499 is three times more likely to attend college and four times more likely to graduate than a student from a similar household with no savings.

“Ms. Garcia says she hears about the savings penalty myth all the time, so much so that she recently took to her blog to try to explain it away with some numbers ...“Not saving for college penalizes you a whole lot more,” she said.”

How to Save for College Rules of Thumbs

So, how much should your family save? Here is my rule of thumb. Or rules of thumbs.

First rule: toss out the saying, “Save for retirement, because you can take out loans for college.” That’s a significant part of how we got to the point of over $1.5 trillion in outstanding student loans. College is one of your priorities and needs to be treated like one. Which is to say, the question isn’t “Should I save for retirement or for college?” but “How do I balance saving for retirement and college?”

Here’s how.

If you are not contributing to retirement at all, you should also not be contributing to college. Instead, any spare dollar you have needs to go to retirement. College savings should only be funded through “extras” – tax refunds, bonuses, gifts and the like.

If you are contributing but not maxing out retirement savings – this means contributing at least the maximum annual allowable 401k contribution, currently $19,500 for those under 50 and $26,000 for those 50 and over – then you should save 10% of what you’re contributing to retirement for college.

Let’s break that down. If you save, for example, $10,000 annually for retirement, you should save $1,000 annually for college. As your savings capacity grows, keep that 10% to college ratio in place until you are maxing out your retirement contribution (the amounts above). Only then should you increase your college savings rate.

If you are already maxing out retirement savings and can contribute more than 10% of your retirement savings to college, how much to save depends on your children’s ages and your education funding goals. Young families should target their state’s tax-deductible 529 contribution amount or an amount that will grow to a target annual funding amount such as $20,000 per year (meaning a 529 account worth about $80,000 at high school graduation).

There are of course lots of variables that might influence whether or not these targets are best for you personally. A rule of thumb is really just a way to think about something; it’s not a diktat.

Second rule: if your college savings balance is more than 20% of your retirement savings balance, you might be overemphasizing college savings and putting your retirement savings at risk. In this case, take a pause on contributing to the 529 while you refocus on retirement. And again, your circumstances may be different but neither college saving nor retirement saving should come at the expense of the other.

Third rule: Setting that aside, a recent New York Times article has some good suggestions for simplifying the college savings process. Among them:

Multiply your child’s age by $2,000 to have a sense of how much you should have saved for college by now. For example, if your child is 12, you should have $24,000 saved.

Saving earlier is easier than saving later.

Many families end up using the 1/3-1/3-1/3 approach to paying for college: 1/3 is paid from savings, 1/3 from income/cash flow, and 1/3 from borrowing.

Making a college savings plan that actually works

Here’s how to get started: As early as you can in your child’s life, figure out a monthly amount you can afford to put towards college. That amount may be your plan’s minimum, which is typically $15 or $25. Then set up that monthly contribution as an autopay. If you don’t want to look at investment choices, choose the age-based portfolio for your child’s age. Worst case, you never look at it again and by the time your child is ready for college, you’ll have about $10,000 in savings.

You might find that you’re like most families and your finances aren’t exactly linear. If your child is young, you’re juggling childcare costs and perhaps one parent has stepped back from their career for a while. There will almost certainly be other unexpected changes and expenses along the way that compete with the family budget. That’s all just fine as long as you keep your autopay going at some affordable amount.

But good changes happen too: a promotion or bonus, or kids going to school full-time and freeing up money that went to childcare. Good planning acknowledges that all of those things can happen, and it works to minimize the degree to which lifestyle creep is permitted to take over your surplus. You may have heard the phrase “pay yourself first.” This applies to college savings as well as retirement savings. When you automate your savings, you automatically remove those dollars from your household budget so they’re going to college savings, not Amazon or dinner out. Unfortunately, unlike some 401(k)s that automatically increase your contribution, you have to do this manually for your college savings.

Automating savings also helps to keep lifestyle creep from preventing you from growing your savings. With your 401k it’s automatic: get a raise, and if you’re contributing a percent of pay to your 401k you’ll automatically be contributing more each paycheck. You need to manually increase your 529 contributions to keep up. I’d suggest that you review your autopay 529 contribution annually during the month of your child’s birthday. That’s a great time to think about the future you’re trying to create for them and make a birthday gift of a higher monthly contribution to support that vision.

Once you’ve automated your contributions, you can also make lump sum contributions should circumstances allow it. In-laws give cash gifts for birthdays or holidays? Put some or all of it into the 529. Got a bonus or a tax refund? Make a 529 contribution. Got a little extra cash at the end of the year? Putting some of it into your 529 in December might save you on taxes come April.

Remember that doing something is always better than doing nothing. It’s okay to start small – just keep reassessing and know that you’ll keep upping your contribution as you go.

Why Saving Early for College is So Important

A 2017 Sallie Mae study showed that on average, parents begin saving for college when their child is 7 years old. This makes sense: it’s right around when a child transitions from preschool or full-time daycare to full-time school, so it’s likely the first time that they have any financial breathing room.

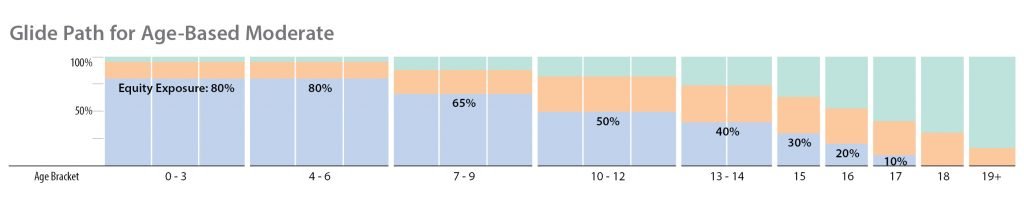

But while it’s logical that starting early on retirement savings yields much better results than waiting, it’s less well-known that starting early on college savings provides even more dramatic results. The logic behind either of these is simple: The more time your money has to compound, the greater the future value. And 529 saving portfolios have even more significant benefits to early savings: Because their glide paths are quite compact, missing out on early savings years means missing out on the most aggressive growth years.

An age-based portfolio in a 529 account is similar to a target date fund in a retirement account in that investments follow a glide path where they start out aggressive and over time, as the saver approaches the target, become more conservative. 529s differ as their lifecycle is compressed to a maximum of 18 years— 529 account may go from 90% stock to 100% fixed income over just 18 years.

Here’s the Utah Education Savings Plan’s glide path, starting 18 years from college:

So parents who wait until age 7 to begin saving miss out on the potentially highest-returning years of a college savings plan. In fact, in the Utah plan, the 0-3 year age-based moderate option’s average annual return has been at least 1% higher than the return for the 7-9 year band on a 3-, 5-, and 10-year basis and since inception.

How does that play out over time? Let’s say a family saved $10 per month for college using the Utah plan’s moderate option. If they started at the beginning of each age band and earned the average return each year, here is what their 529 account would be worth at high school graduation:

| Start Age | Total Contributions ($s) | Balance at 18 ($s) | Growth ($s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2160 | 3789 | 1629 |

| 4 | 1680 | 3102 | 1422 |

| 7 | 1320 | 2007 | 687 |

| 10 | 960 | 1350 | 390 |

| 13 | 600 | 819 | 219 |

| 15 | 360 | 516 | 156 |

| 16 | 240 | 246 | 6 |

So the family who started saving when their kids were born would end up with almost twice as much in the account as the family who started at age 7. Plus, 43% of the balance of the account that was started at birth was account growth– free money– compared with just 34% in the account started at age 7.

Next section: Savings Options

Learn about why 529 savings plans are your best options as well as the benefits and trade-offs of other savings vehicles